UNDERSTANDING HOOF

BALANCE

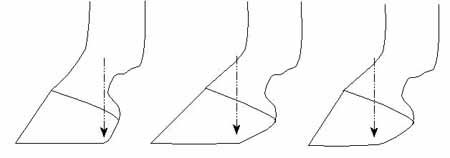

In 1990, at age 15, Cimarron, my TB dressage horse, was retired both from showing and as a pleasure horse. His range of motion had deteriorated until at the trot, even at liberty, his feet barely came past his knees, which themselves failed to pass his chest. He had become a “backwards parallelogram” in motion .

Horse moving in a

mild "backwards parallelogram,"

Horse moving in a

"forwards parallelogram," He also trotted with a shorter right front/left hind diagonal, and suffered chronic back pain and soreness over the hips. Although clinically sound, he was functionally lame. During the previous six years that I’d owned him, he had suffered innumerable hoof abscesses, a variety of mild front leg problems, a hunter’s bump diagnosis, as well as the back pain and irregularity in stride. He had a gorgeous canter, but his trot would rattled me to the bone. Although his conformation suggested otherwise, there were some movements that he had difficulty with and he was a little rebellious when asked to be more correct, which was not consistent with his cooperative attitude. Fairly early on, I suspected that he was resisting out of discomfort, and I did everything I could afford to make him more comfortable: I learned a lot about saddle fit (see Saddlefit article), bought a new, custom-fitted saddle, and tried to ensure that as a rider I was not contributing to his discomfort; he received chiropractic and electro-magnetic therapy, as well as frequent massage and bio-magnetic therapy. Most of it helped—but only short-term. There was obviously something going on that wasn't being identified by the veterinarians I consulted, and I felt I had no choice but to retire him to pasture. Later that fall I attended a horseshoeing clinic and I was stunned to learn that, in spite of regular shoeing by an accomplished and highly-respected farrier, incorrectly balanced hooves were causing most (if not all) of Cimarron’s body soreness, movement and lameness problems. And had been for years. The hoof imbalances were corrected as much as possible, and his movement immediately improved—dramatically. Within days he once again became a “forward parallelogram”! Over the following years, as his feet improved, he became sounder than I’d ever seen him, working well under saddle—softer, happier and keen—and gradually unlocking his back and hips after years of discomfort. His feet are not perfectly shaped even now, and probably will never be, but I keep a close eye on his hoof balance and they have improved enough to make him a different horse. As he entered his twenties, despite the seemingly endless problems he experienced in his early teens, he became more supple and more athletic than at any other time in the 12+ years he had spent with me. My big-hearted thoroughbred had been granted a new lease on life as a direct result of changing his feet! Today, in spite of a severe accidental trauma to his left hind leg at age 24, he comes out of his stall in the mornings more supple than many horses half his age often in a beautiful, effortless extended trot, something he couldn’t even do 10 years ago. Front to Back

Imbalance

Underrun heels frequently accompany long toes, and because the heels tend to be crushed, circulation to the foot is impaired and frequent foot abscesses may result, which can also require several weeks to resolve. Unless these underrun heels are supported by a shoe that extends under the bulbs, the suspensory apparatus is stressed, and a variety of soundness problems can result. Other problems can result from long toes combined with comparatively short shoes. For example in the forefeet, if a plumb line dropped down the center of the cannon when the leg is vertical falls behind the back of the shoe, in motion the opening of the knee is blocked and the horse may trip, or adopt an over at the knee stance. Return to Riding Theory

Main Page Email : rafalet2ride@yahoo.ca | Home | Lusitanos | Equine

Biomechanics & Riding Theory | Last updated October 17, 2003 All rights reserved |